- Authorized assays for viral testing include those that detect SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid or antigen.

- Viral (nucleic acid or antigen) tests check samples from the respiratory system (such as nasal swabs) and determine whether an infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is present.

- When viral RNA is detected in other kinds of samples (such as stool) it should not always be presumed that the patient from whom the specimen was obtained is actively infected or presently shedding virus.

- It is typically presumed that a positive test indicates the patient is actively infected and is also capable of spreading the virus.

- Viral tests are recommended to diagnose acute infection.

- Testing the same individual more than once in a 24-hour period is not recommended.

- The CDC does not currently recommend using antibody testing as the sole basis for diagnosis of acute infection, and antibody tests are not authorized by the FDA for such diagnostic purposes.

- In certain situations, serologic assays may be used to support clinical assessment of persons who present late in their illnesses when used in conjunction with viral detection tests.

- In addition, if a person is suspected to have post-infectious syndrome (eg, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children) caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, serologic assays may be used.

- Clinicians should use their judgment when interpreting tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection (particularly early in the course of infection). If clinical suspicion is high, infection should not be ruled out on the basis of RT-PCR alone (especially when results are being used as a basis for removing precautions intended to prevent onward transmission.

- Studies have reported that testing people for SARS-CoV-2 too early in the course of infection may result in a false negative test, even though they may eventually test positive for the virus.

SARS-CoV-2 Viral Mutations: Impact on COVID-19 Tests

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has mutated over time, resulting in genetic variation in the population of circulating viral strains over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Molecular, antigen, and serology tests are affected by viral mutations differently due to the inherent design differences of each test.

FDA Information for Health Care Providers

Clinical laboratory staff and health care providers should be aware that false negative results may occur with any molecular test for the detection of SARS-CoV-2, particularly if a mutation occurs in the part of the virus' genome assessed by that test. The FDA recommends clinical laboratory staff and health care providers who use SARS-CoV-2 tests note the following:

- Genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2 arise regularly, and false negative test results can occur.

- Consider negative results in combination with clinical observations, patient history, and epidemiological information.

- Consider repeat testing with a different EUA authorized or FDA cleared molecular diagnostic test (with different genetic targets) if COVID-19 is still suspected after receiving a negative test result.

- Test performance may be impacted by certain variants.

- Tests with single targets are more susceptible to changes in performance due to viral mutations, meaning they are more likely to fail to detect new variants.

- Tests with multiple targets are more likely to continue to perform as described in the test's labeling as new variants emerge. Multiple targets means that a molecular test is designed to detect more than one section of the SARS-CoV-2 genome or, for antigen tests, more than one section of the proteins that make up SARS-CoV-2.

- In addition to these general recommendations, the FDA is providing information related to specific variants and recommendations for the use of specific tests that may be impacted by genetic variation in the sections below.

NIH Guideline Testing Recommendations:

- To diagnose acute infection of SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines recommend using a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) with a sample collected from the upper respiratory tract (i.e., a nasopharyngeal, nasal, or oropharyngeal specimen) (AIII).

- For intubated and mechanically ventilated adults who are suspected to have COVID-19 but who do not have a confirmed diagnosis:

- The guidelines recommend obtaining lower respiratory tract samples to establish a diagnosis of COVID-19 if an initial upper respiratory tract sample is negative (BII).

- The guidelines recommend obtaining endotracheal aspirates over bronchial wash or bronchoalveolar lavage samples when collecting lower respiratory tract samples to establish a diagnosis of COVID-19 (BII).

- A NAAT should not be repeated in an asymptomatic person within 90 days of a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, even if the person has had a significant exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (AIII).

- SARS-CoV-2 reinfection has been reported in people who have received an initial diagnosis of infection; therefore, a NAAT should be considered for persons who have recovered from a previous infection and who present with symptoms that are compatible with SARS-CoV-2 infection if there is no alternative diagnosis (BIII).

The guidelines recommend against the use of serologic (i.e., antibody) testing as the sole basis for diagnosis of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (AIII).

- The guidelines recommend against the use of serologic (i.e., antibody) testing to determine whether a person is immune to SARS-CoV-2 infection (AIII).

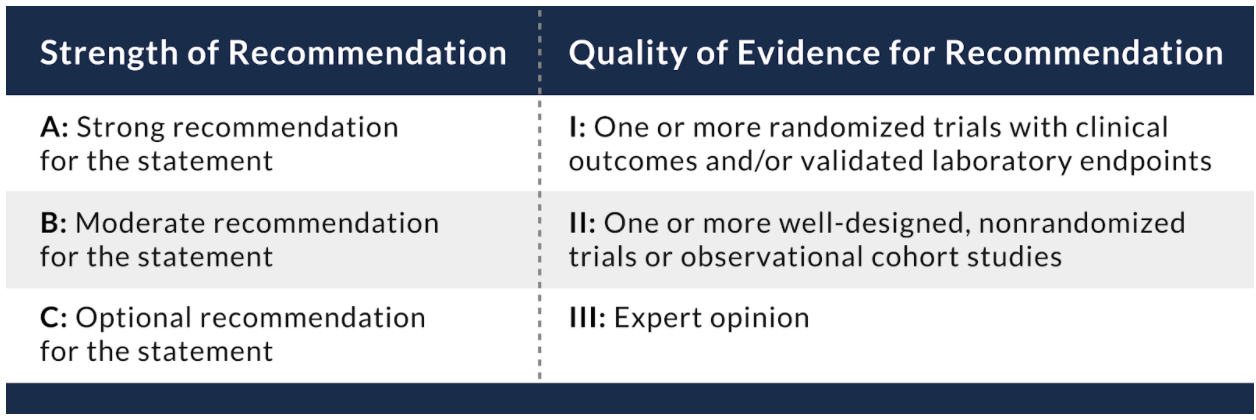

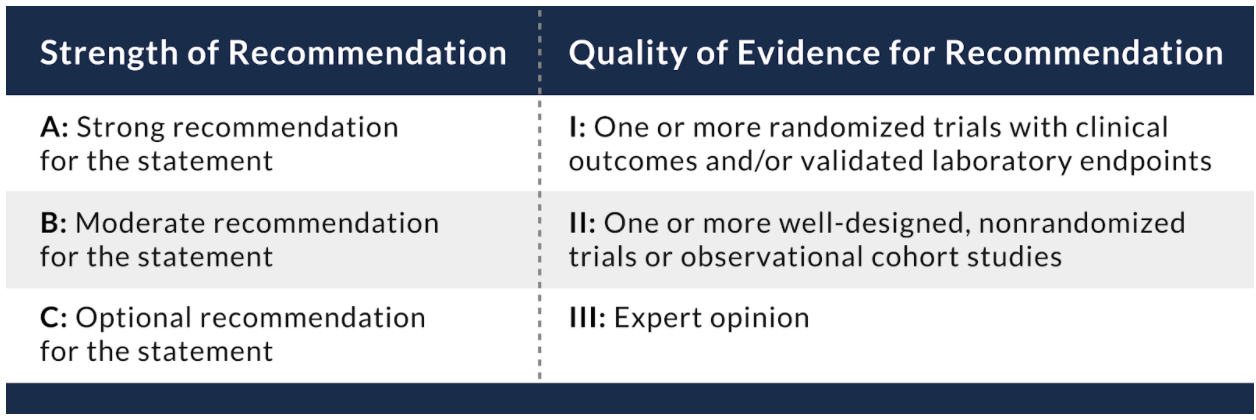

Table 8.1 Recommendation rating scheme.

For more information see the NIH Guidelines for Testing for SARS-CoV-2 Infection.

Testing Guidance from CDC:

The following people who should tested for a current COVID-19 infection:

- People who have symptoms of COVID-19.

- Most people who have had close contact (within 6 ft for ≥15 min over a

- 24-hr period) with someone with confirmed COVID-19.

Fully vaccinated people with no COVID-19 symptoms do not need to be tested following an exposure to someone with COVID-19.

- People who have tested positive for COVID-19 within the past 3 months and recovered do not need to get tested following an exposure as long as they do not develop new symptoms.

- Unvaccinated people who have taken part in activities that put them at higher risk for COVID-19 because they cannot physically distance as needed to avoid exposure, such as travel, attending large social or mass gatherings, or being in crowded or poorly-ventilated indoor settings.

- People who have been asked or referred to get tested by their healthcare provider, or state, tribal, locale, or territorial health department.

CDC recommends that anyone with any signs or symptoms of COVID-19 get tested, regardless of vaccination status or prior infection. If you get tested because you have symptoms or were potentially exposed to the virus, you should stay away from others pending test results and follow the advice of your health care provider or a public health professional.

Testing Strategies for COVID-19:

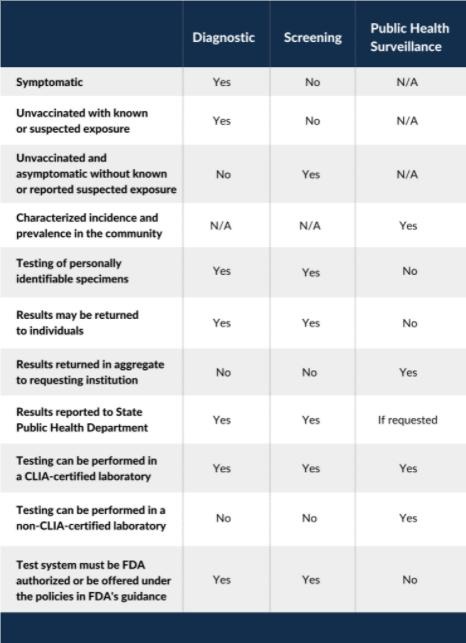

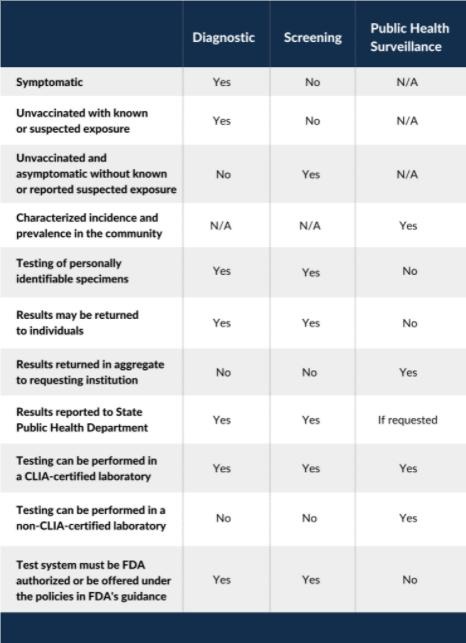

Diagnostic Testing

- to identify current infection in individuals and is performed when a person has signs or symptoms consistent with COVID-19, or when an unvaccinated person is asymptomatic but has recent known or suspected exposure to SARS-CoV-2.

Screening Testing

- to identify unvaccinated people with COVID-19 who are asymptomatic and do not have known, suspected, or reported exposure to SARS-CoV-2.

- helps to identify unknown cases so that measures can be taken to prevent further transmission.

Public Health Surveillance Testing

- ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice.

- intended to monitor community- or population-level outbreaks of disease, or to characterize the incidence and prevalence of disease.

- Public health surveillance testing results cannot be used for individual decision-making.

Regulatory Requirements for Testing

- Any laboratory or testing site that performs diagnostic or screening testing must have a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certificate and meet all applicable CLIA requirements.

- Tests used for SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic or screening testing must have received an EUA FDA or be offered under the policies in FDA’s Policy for COVID-19 Tests.

- Tests used for SARS-CoV-2 public health surveillance on de-identified human specimens do not need to meet FDA and CLIA requirements for diagnostic and screening testing.

Reporting Testing Results

- Both diagnostic and screening testing results should be reported to the people whose specimens were tested and/or to their healthcare providers.

- In addition, laboratories that perform diagnostic and screening testing must report test results (positive and negative) to the local, state, tribal, or territory health department in accordance with Public Law 116-136, § 18115(a), the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

- Public health surveillance testing results cannot be reported to the people whose specimens have been tested and are not reported to their healthcare providers.

- Public health surveillance testing results (test results that are de-identified) can be reported in aggregate to local, state, tribal, or territory health departments upon request.

- Results from testing that is performed outside of a CLIA-certified facility or without an FDA-authorized test can only be reported to a health department if those results are used strictly for public health surveillance purposes, and not used for individual decision making.

Table. Summary of Testing Strategies for SARS-CoV-2

The FDA has also published the Comparative Performance Data for COVID-19 Molecular Diagnostic Tests. The tables in the publications show the Limit of Detection (LoD) of more than 55 authorized molecular diagnostic COVID-19 tests against a standardized sample panel provided by the FDA.

- A lower LoD represents a test’s ability to detect a smaller amount of viral material in a given sample, signaling a more sensitive test.

- However, the data does not indicate how sensitive a particular test is, and, therefore, cannot be used by itself to determine whether to authorize a test or other regulatory action.

Health care providers should contact their local and state health department immediately to notify them of patients with fever and lower respiratory illness who they suspect may have COVID-19, and local and state public health staff will determine if the patient meets the criteria for testing for COVID-19.

References

- Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting Diagnostic Tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2249–2251. DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.8259

- Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. [published online ahead of print, 2020 April 1] Nature. 2020. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x

- Hadaya J, Schumm M, Livingston EH. Testing individuals for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 1]. JAMA. 2020;10.1001/jama.2020.5388. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5388

- Nandini Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting Diagnostic Tests for SARS-CoV-2. [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 6]. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2249-2251. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8259

- Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J. Variation in False-Negative Rate of Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction–Based SARS-CoV-2 Tests by Time Since Exposure. [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 13]. Annals of Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1495

Table 8.3 Questions to ask individuals being tested for COVID-19.

Brief Reminder Regarding Diagnostic Test Interpretation

Author: Jessica Whittle, MD, PhD, FACEP, Director of Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Tennessee College of Medicine

Most clinicians understand the value of sensitivity and specificity when considering the utility of a diagnostic test. These characteristics are inherent to the test itself and independent of the prevalence of the disease being considered.

- Sensitivity (also called the true positive rate, the epidemiological/clinical sensitivity, the recall, or probability of detection in some fields) measures the proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified as such (eg, the percentage of sick people who are correctly identified as having the condition).

- Specificity (also called the true negative rate) measures the proportion of actual negatives that are correctly identified as such (eg, the percentage of healthy people who are correctly identified as not having the condition).

- A test that is 95% sensitive and 95% specific would be considered a good test by most clinicians. This means that if samples taken from 100 people with disease are tested, 95 of them will test positive. Conversely, if samples taken from 100 people without disease are tested, 95 of them will test negative.

- However, the challenge comes when there is only a single patient before you, not 100. To know if the positive sample in front of you is one of the true positives, or one of the false positives, prevalence must be considered. Positive predictive value allows the clinician to consider this.

- Utilizing the example above, in an area in which 2% of the population is infected we find the positive predictive value (PPV) is 28%. If you tell a patient their positive test is a true positive in this circumstance, you could be wrong as many as 72 times out of 100.

- However, when the disease prevalence is 25% in the population, you will find that the PPV is 87%. In this instance, if you tell the patient that their positive test is a true positive, you will be correct 87% of the time. You could be wrong as many as 13 times out of 100.

For more information on how to best consider and relay test information to your patients, please look to the resources developed by our colleagues: